At the end of the 2000s, social networks revolutionized the way of communicating and doing politics in electoral campaigns. This revolution meant that both the candidates’ platforms and the electorate would change their way of relating within the field of politics.

Since then, a new phenomenon has emerged that does not promise, but is already, the next new paradigm shift when it comes to campaign communication: Artificial Intelligence.

This technology is not new in the field of politics. In 2016, Cambridge Analytica’s participation in Donald Trump’s presidential campaign highlighted the usefulness of data automation and microtargeting, a way to reach each individual with a personalized message for them.

The advancement of automated tools has been exponential since the launch of Chat GPT, the best-known AI program, in November 2022. Since then, the level of development and quality of content generated with the help of artificial intelligence has become increasingly less distinguishable.

The Argentine presidential election in 2023, which is defined today between Sergio Massa and Javier Milei, is an international case study for the various uses of artificial intelligence in political campaigns.

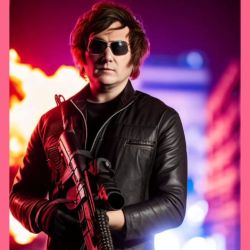

Campaign posters presenting candidates as heroes, caricatures that present them as monsters, deepfakes that deceive the electorate, and forged audios are some of the uses that can be put to these tools.

But campaign teams are not the only ones using these tools. The greatest use comes from militants and supporters who generate content for and against the candidates.

Accounts like IAxLaPatria, which claim to be unofficial, constantly shared images with political connotations created through Generative Intelligence programs. Stable Diffusion was one of the programs used, within which by entering a specific slogan you can generate an image that represents what is communicated to you.

Until now these uses are normal within an electoral dispute. The problems begin when AI is used for disinformation.

During the electoral period, several images created using artificial intelligence circulated that portray the candidates in fictitious situations. The content that had the biggest stir was a video edited with Sergio Massa’s face where he was seen consuming cocaine.

That false video created by superimposing images of the official candidate through a program was part of the dirty campaign. and although the veracity of the content spread on networks like X (previously Twitter) was quickly denied, it proved that one of the biggest challenges when dealing with artificial intelligence is the confirmation bias of those who consume this type of content. .

The so-called fake news, or misinformation, has been a problem for years. False information not only spreads like wildfire, but it is also very difficult to deny it in time.

What are other problematic cases? The parliamentary elections in Slovakia served as a case study for these situations. On the eve of the electoral process, at the end of September, AI-produced recordings between a candidate from the Slovak Progressive Front and a journalist were published on Facebook.

This audio discussed fraudulent electoral tactics and ways of buying minority votes within the country. The speed and effectiveness of these manipulations make it extremely difficult to deny them in time.

Experiences like these demonstrate the need to find better defenses against the influence of AI in politics and the importance of regulations in the digital age.

Experiences like these demonstrate the need to find better defenses against the influence of AI in politics and the importance of regulations in the digital age.

The United States Federal Electoral Commission is debating the regulation of the use of Artificial Intelligence in spots ahead of the 2024 presidential election. This debate arose after a video published by the Republican Party that purely uses images generated by AI to call to fear of the re-election candidacy of the current North American president Joe Biden.

What is the biggest challenge? Detect, deny and control disinformation that becomes more credible and effective every day thanks to new methods. Work that previously took experts weeks to develop can today be done by an amateur in a few hours.

From a political point of view, it is necessary to train, educate and educate citizens about possible manipulation and rampant misinformation. “Seeing is believing” is no longer enough.

by Luca Benaim